“The Painting of a picture is no aesthetic matter. In so far as it is possible I would like it to be a communication from heart to picture and then from picture to heart, wherever such a contact is allowed”

Hermann Gross, January 1985. (Camphill Correspondence, 1989) cited Robin Jackson ‘Art and Soul'

Hermann Gross was born in Germany on the 4th of February 1904 in Lahr, Baden-Wurttemberg, located close to the French border. At the age of 6 his family moved to Stuttgart, where he became a pupil at the Realgymnasium. Gross was a very creative child and at an early age he dreamed of becoming an artist. His father agreed with the prerequisite that he learn a practical skill to fall back on. Gross complied and after school he trained at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Art and Crafts School) as a Gold and Silversmith from 1919 to 1925. This foundation taught him an attention to detail which is apparent in his later sculptural works. During this time, Gross was fortunate to serve as an apprentice under some of the most prominent craftsmen in their respective fields within Europe.

Learn more about Hermann's Teachers

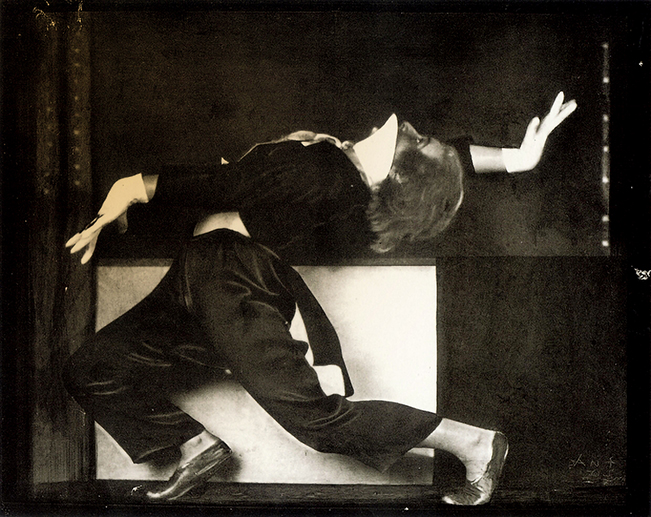

As a young man, Gross was an independent thinker with his own unique sense of style. He was an enthusiastic dancer and was attracted to the Expressionist dance movement that was prominent during the 1920s and 30s in Germany. In contrast with the constraints of everyday German life, it was a liberal space for men and especially women to be themselves.

Gross integrated himself into this space by joining a dance group and performing onstage, sometimes naked, and in a mask. Masks would play a recurring role throughout Gross’ creative work.

As a self professed ‘hippy before his time’, Gross found his home in this liberating cultural movement. Yearning for more of this creative, alternative lifestyle, Gross like many artists of his time, found himself drawn to Paris.

“In most countries, when people are faced with hard times, the arts suffer. When people struggle for their daily existence, art has to take a back seat. But not in France” Hermann Gross

( Jackson 2008:22)

In 1928, Gross and his partner, fashion illustrator and writer, Hildegard Friedrichs moved to Paris. They lived in a run-down studio at 48 Avenue des Gobelins bordering Montparnasse. Although times were tough, Gross seemed to enjoy the chaotic creativity of his daily life. He filled his studio with soldering equipment, vices and metalworking tools. Sketches covered his walls and an iron wire dodecahedron hung from the ceiling, which he used to check the scale and balance of the sculptures he was working on.

Whilst in Paris, Gross befriended and worked with a remarkable group of young up-and-coming artists, writers and actors. He knew Picasso, Matisse, and most likely Chagall and Braque. Gross greatly admired artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka and George Rouault, among others. Gross was a student of German Expressionism, an art form where distortion and exaggeration are used for emotional effect. It is a style that fought against the more conservative art style that was prominent at the start of the 20th Century. German Expressionist art is highly subjective. Its use of intense colour, rough brush strokes and disjointed space aim to elicit an emotional response from viewers rather than to portray a sanitised version of reality.

Learn More about german expressionismGross continued to work on his art and in 1929 he exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. The first Salon d’Automne had been set up by Matisse, Derain and Rouault in 1903 as a response to the much more conservative Paris Salon. It soon became a centre of new and experimental sculpture and painting. Here Gross presented a metal sculpture titled ‘ Portrait de jeune Fille Repoussé sur cuivre’. Gross’ time in Paris was an artistically fulfilling time for him and one he remembered fondly in his later years. The next chapter of his life was to be very different.

In 1935 Gross returned to a Berlin now under Nazi Control. His return was primarily prompted by his father’s ailing health. Additionally Gross and Hildegard Friedrichs had ended their relationship and Gross was feeling lonely and missing his German Friends. Gross and a friend, Hans Haustein, rented an attic studio in North East Berlin. His building was also the home to other freethinkers that the Nazis saw as problematic, such as Marxist Theodor Plivier who would go on to write the classic anti-war novel Stalingrad in 1948. Gross’ creative character attracted like minded people and his studio soon became a meeting place for artists, journalists, philosophers and publishers.

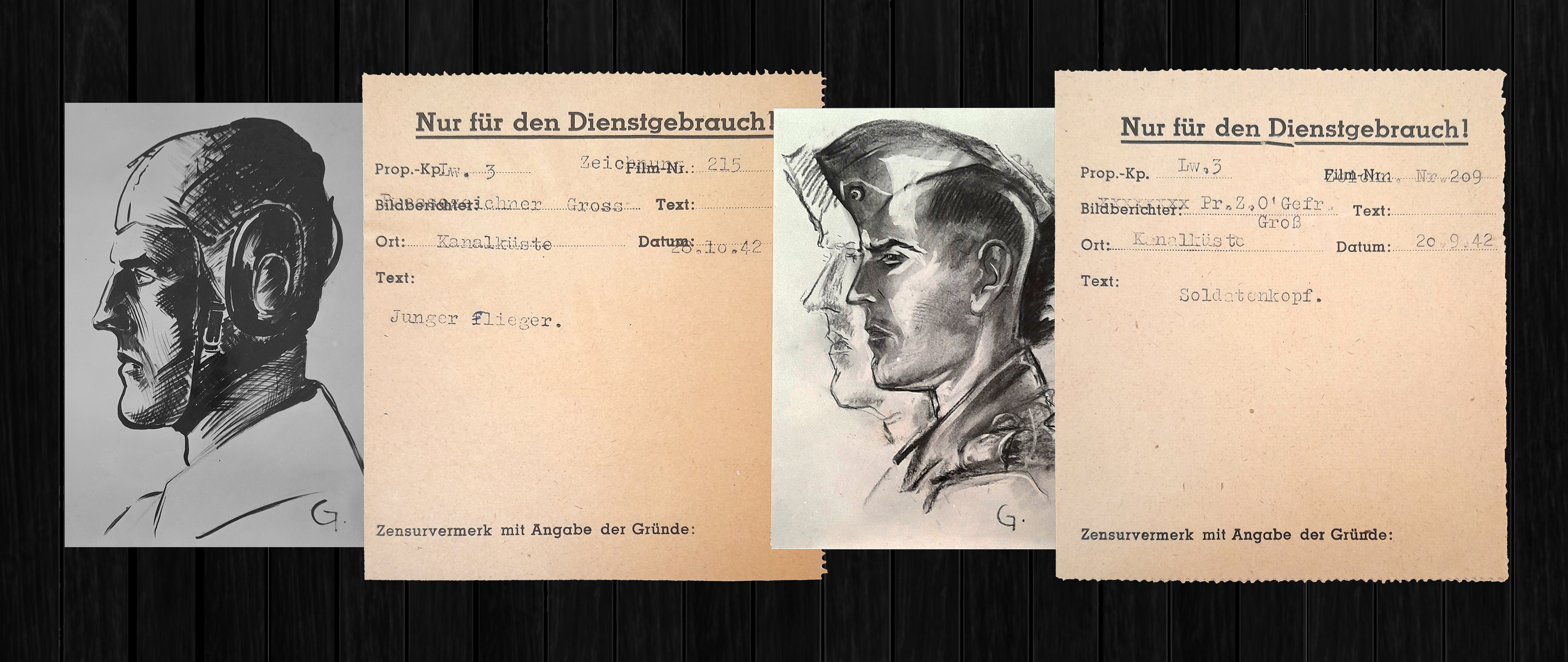

Gross was conscripted into the Luftwaffe as an air gunner in 1941. He was medically discharged before he saw any action. This discharge was possibly due to Gross being deemed psychologically unfit for the task. His background as an artist would have had an influence on where he was subsequently stationed. Being deemed unfit as an air gunner, Gross was transferred to one of Goering’s Propaganda Companies based in Paris.These companies consisted of photographers, reporters, cameramen, radio commentators and artists. Gross was sent to Luftwaffe Propaganda-Kompanie 3, where he worked as a ‘ Pressezeichner’, a Press draughtsman or war artist.

Photographs taken by Gross of sketches he did during the war whilst a war artist. The first of a soldier and the second of an airman. On the back of these sketches are the original Luftwaffe tickets where Gross’ unit and job title can be seen. These photographs were found amongst Gross’ personal papers by Robin Jackson (2008).

As a member of a propaganda unit, Gross’ main directive was to distort truth. One of his many tasks was to cut out aeroplanes from air battle photographs. He would then reposition them to make it look like the German side was winning and re-photograph the image. These images were then printed in the newspapers and presented as ‘the truth’ in order to boost German morale.It must have been a very surreal situation for Gross to be in. He was back in Paris, a place he loved dearly. However the art world he had been so immersed in was now very much under threat. Worse still, he was now forced to be an accomplice to this destruction.

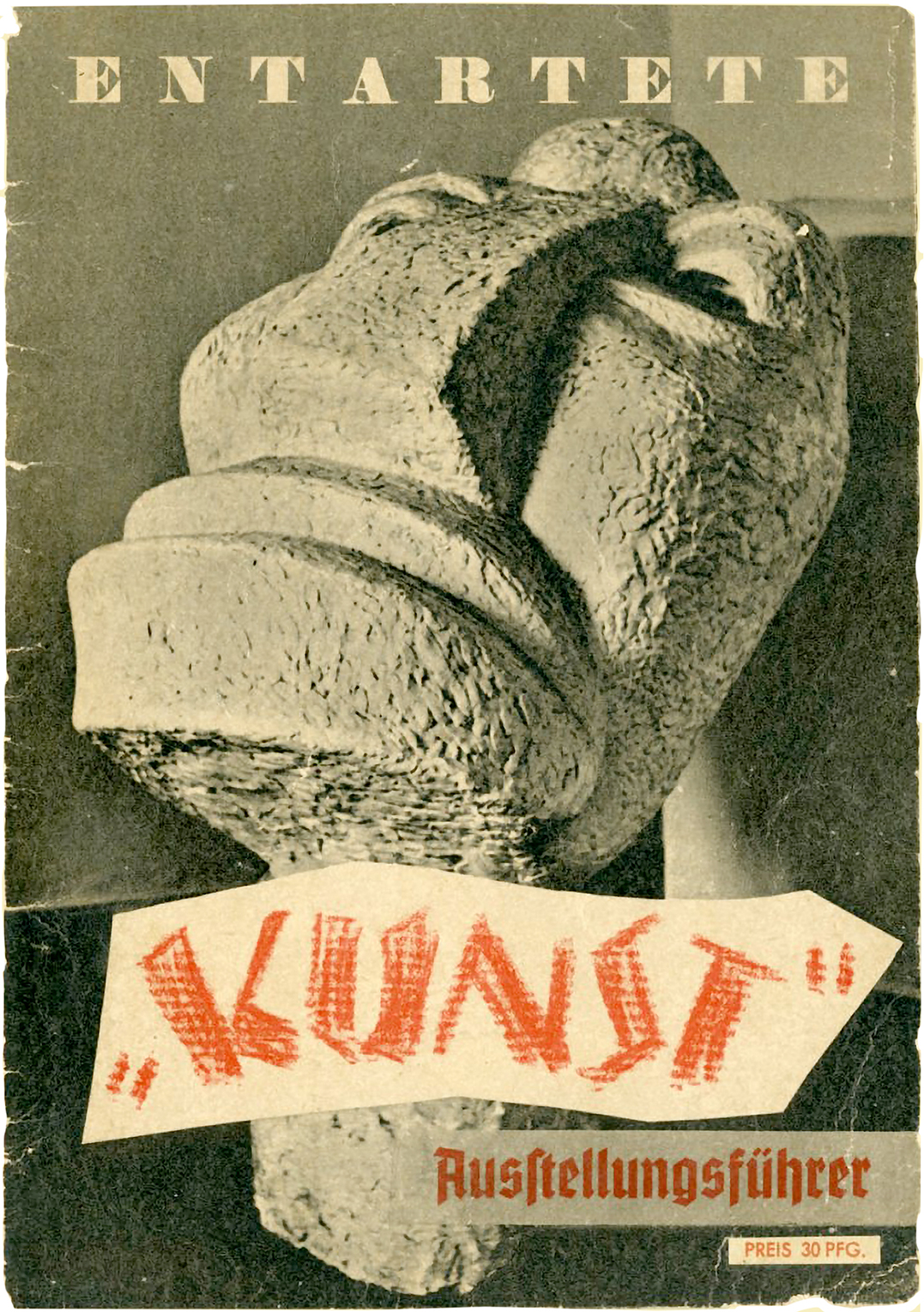

The Weimar Republic period (1919-1933) was a time of great change in Germany. The end of monarchy rule and the establishment of a new constitution led to a much freer society. Freedom of speech and expression were encouraged and this led to the emergence of new artists and art styles, chief among them German Expressionism. Gross and many of his contemporaries were immersed in this new movement and it was this movement that became so abhorrent to the emerging Nazi Party.

The end of the Weimar Republic era was brought on by the Great Depression of 1929. Germany entered great economic hardship and suffering and it was from this suffering that the Nazi Party found its footing. The Party used Culture as a propaganda tool and preferred art that was simpler and more conformist. Classical Greek, Roman art or German Impressionism was preferred.

This art was seen as more traditional and less open to interpretation. The Expressionist, ambiguous art from the Weimar Republic period was a complete anathema to that. The Nazis saw it as a time of too much Jewish representation and Communist tendencies, a time of moral decay and decadence.

It was for this reason that the art and artists of this era were branded ‘Degenerate’ and much effort was spent in destroying or confiscating artworks and silencing artists.

A picture of Goebbels visiting the ‘Degenerate Art’ show in 1937 in Munich. The front cover of the brochure for that show was designed by the Nazi propaganda central office. The aim was to make the art displayed look as ‘primitive’ as possible. Note the child-like font of the word ‘Kunst’, the way it looks rushed and roughly put together along with the unflattering photo of the sculpture.

This is the environment that Gross was now existing in. His dilemma would have been exacerbated by the fact that the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenburg (ERR) was also operating in Paris at this time (1940-44). The ERR was a Nazi office set up by Alfred Rosenberg in 1940 and later controlled by Hermann Goering. Its purpose was to confiscate or destroy thousands of important books, documents and artworks, especially any created by Jewish artists or artists that the Nazis deemed ‘degenerate’. This was initially done under the pseudo academic objective of ‘studying’ Jewish culture but soon descended into theft and destruction. This included art by many of the artists Gross had known and admired including Chagall, Picasso and Matisse. The ERR was located in the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris and received military support from Goering and the Luftwaffe. It is believed to have looted more than 21,000 individual objects from over 200 Jewish-owned collections.

Hitler examining paintings confiscated by the ERR. Top right, the ERR official stamp.

The fact that Gross was a witness to, and indirectly involved in, the suppression and destruction of art in Paris, his creative home, must have been deeply distressing to him. Throughout these years Gross leaned more into his Christian beliefs as a way of coping with the destruction and hateful ideologies that surrounded him.

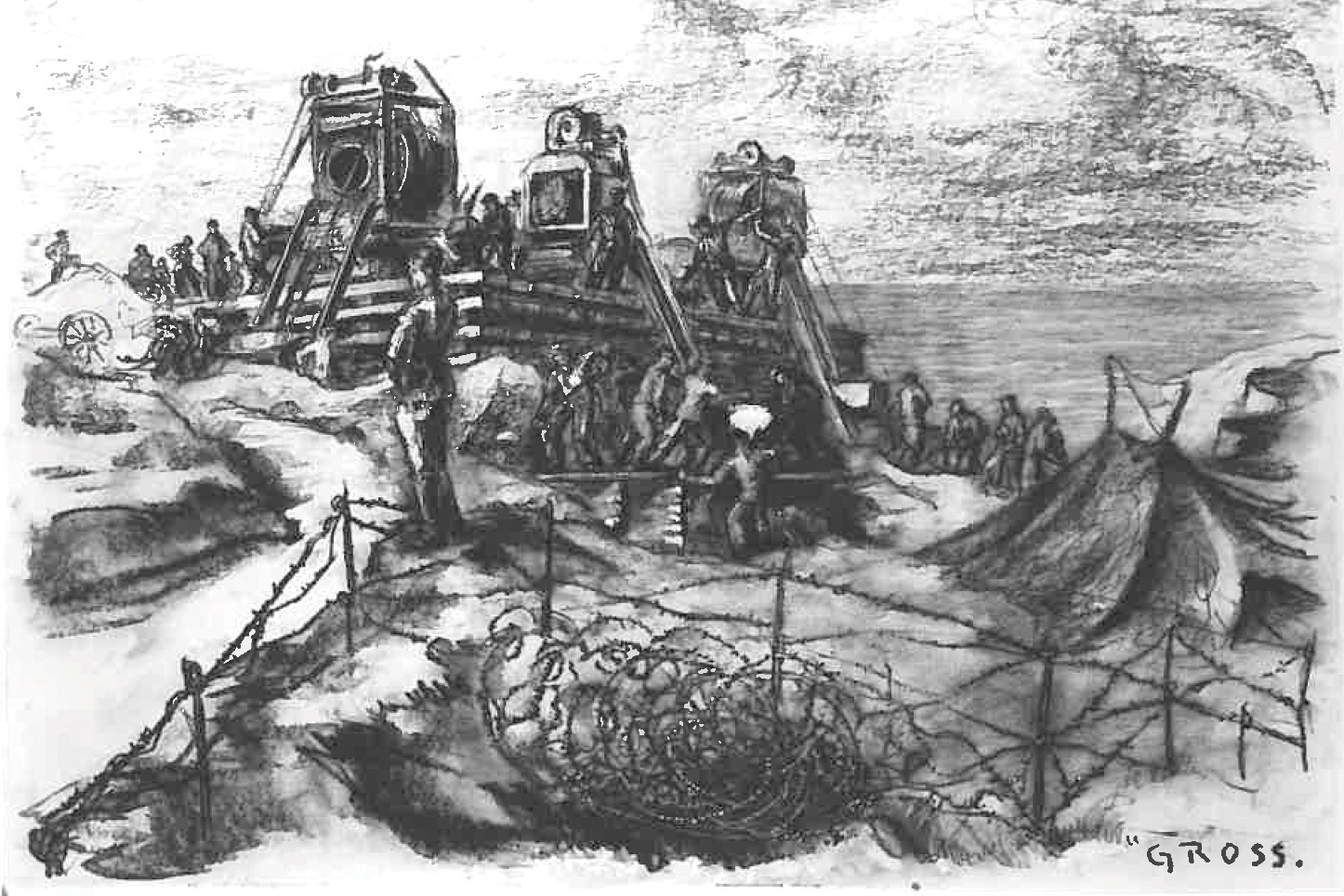

Soon Gross left Paris and was tasked with sketching out the defences Hitler had ordered along the northern French coast, also known as Hitler’s ‘Atlantic Wall’. Work on these defences took place between 1942 and 1945 and consisted of immense concrete fortifications and bunkers.

Although it would have been dangerous for Gross to speak up against what was going on around him, hints at his opposition can be gleaned from some of these sketches. Robin Jackson, the author of ‘Hermann Gross: Art and Soul’ (2008), had the following observation:

“...it is what lies beside the bunker that catches our attention. Is it accidental that in this sketch the discarded planks that lie alongside the bunker have fallen in the shape of a cross? At the top of the central plank there is a circle of barbed wire. Is it too far fetched to imagine this as the crown of thorns on Christ’s brow?[...] In studying the planks entangled in the barbed wire, is it also possible to detect a distorted Star of David swathed in barbed wire? Might this be an allusion to the internment of Jews and others in concentration camps?”

(Jackson, 2008).

.jpg)

During this time Gross became increasingly fixated on the Crucifixion with its themes of death and destruction but also of rebirth, resurrection and hope. Jackson suggests that this can be glimpsed in the sketch above where the position of three concrete mixers situated on a hill are reminiscent of Calvary, the site where Jesus was crucified. This theme of the crucifixion was to feature heavily in Gross’ work after the war.

Towards the end of the war Gross was sent to the Eastern Front where he served as a guard for command headquarters. It was a miserable experience for him and at the end of the war Gross made his way back to Germany.

This whole period in his life greatly affected Gross’ Psyche and left him traumatised. Much of Gross’ art in the next period of his life would reflect this trauma in dark, sombre religious drawings and paintings. The theme of the crucifixion would appear repetitively.

“Out of the nothing of the devastation of Europe, it seems to me that the bible and its message is a salvation. There is nothing which is not reflected there…their symbolisms are everlasting and modern in their significance…to give form to these everlasting themes is for me a resurrection”

( Hermann Gross, excerpt from a brochure for his exhibition at the Macbeth Art gallery in New York, 1948, (Jackson, 2008).

When Gross returned to Germany after the war he was depressed and worn out. He continued to create sculptures, drawings and paintings in an attempt to return to some normality.

In 1946 Gross had an exhibition at the Art House in Freudenstadt. This was to be an important moment in his life. The Art House was run by Hildegard Rath, a successful artist in her own right and from a very creative family. Gross and Rath soon struck up a relationship.

In 1946 Gross and Rath moved to Paris. However, this return to Paris was a challenging one for Gross. The Paris he had once known was now gone. Additionally, Gross, as a German, may not have been made feel as welcome as he once had. Gross and Rath married in 1948 and that same year they left France for America. They initially moved to Vermont to join members of Rath’s family but soon alternated between New York City and Vermont. This was mostly due to Rath’s artistic career which was much more successful than Gross’. Through her connections Rath also worked as an advocate for Gross’ art. She was able to secure an exhibition for him at the Macbeth Gallery in New York in 1948.

_STUDIO.JPG)

_STUDIO.JPG)

_STUDIO.JPG)

His works displayed during this exhibition were Expressionist in style and religious and sombre in nature. Gross’ preoccupation with the crucifixion and the idea of resurrection were apparent. Through his art Gross was trying to process his experiences during the war. The feelings of guilt he may have had about his role in the propaganda unit and, indirectly, in the betrayal of artists he greatly admired. The Christian idea of resurrection was important to him - that new life could emerge from death.

His work was powerful and left an impression with art critics at the time, as one wrote:

Art New: December 1948

“His work, forbidden and branded as degenerate by the Nazis, has passed through the crucible of war-torn Europe and shows in a group of forceful, haunting compositions in watercolour and crayon, the regeneration of deep artistic and moral convictions. His favourite themes are inspired by the Bible, from which he extracts images that run the gamut from a powerful expressionism to geometrically organised abstractions”

In 1951- Gross held his second exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery.His work was still centred around Christianity and the teachings of Christ. As Robert MacIntyre, who owned the Macbeth Gallery commentated at the time:

“ In this, his second exhibition since coming to this country a few years ago, Hermann Gross is still preoccupied with the theme of Christ - His short life on earth, His death and resurrection, but above all His teachings. It is a theme deeply inwoven in his own life. Christ to Gross, was not only a great philosopher but a great psychologist whose profound yet simple principles of the art of living have as much force and application today as in His own time. In this present era of unrest and rampant greed for power and domination in part so much like the dark ages, Gross feels that Christianity, with all its invariable and fundamental ethical principles and precepts, is once again being crucified: that the only means of salvation the world can ever look for if through a renascence (sic) of those same old and abiding principles of moral and spiritual values. But he feels also, that in spite of this casting aside of these, the only true permanent values, we are but going through a time of trial and error: that eventually the black cumulus clouds of dissension and war, of jealousy and greed, will give way to the penetrating light of a new moral perception that this light will reach into the hearts of men, and there give birth to a new earnestness of purpose of living.”

Robert MaIntyre- owner of the Macbeth Gallery 1951, (Kashmiry 2007, cited in Jackson 2008)

This exhibition was also received well with critics as can be seen below:

New York Times: 26 January 1951

“His watercolours now at the Macbeth Gallery use both abstraction and stylisation as means of expression for his religious subjects. Perhaps his greatest gift is a mastery of smoldering and effective color, patches of which get put together like a fluid changing mosaic. Obviously a descendent of the German Expressionists, Gross makes personal use of these idioms. Here is religious painting in a wholly contemporary mode, weakened neither by sentimentality nor adherence to worn-out imagery. The implications reach out into twentieth-century living. Curiously, the more abstract of these paintings seem to have the clearest and most forceful impact”

Gross only had two exhibitions in America and didn't sell much of his work. Although modern for its time, his work was too religious for those interested in modern art and too ‘raw’ for those interested in religious art. To supplement his income, Gross drew on his expertise in metalwork to create props and scenery including metal masks and headgear for theatrical productions.

To supplement his income, Gross drew on his expertise in metalwork to create props and scenery including metal masks and headgear for theatrical productions.

In 1956 a somewhat dejected Gross returned to Germany. He hadn't been successful in America and his marriage to Rath was failing. Through a friend he was re-introduced to a journalist called Trude Sand who had been part of his friend group when he had been living in Berlin. The two hit it off and soon started sharing a studio. Once Gross’ divorce from Rath was finalised, he and Sand married. In 1956 Gross had an exhibition in the Town House in Freudenstadt where he showcased a collection of his paintings, drawings and sculptures. His art was still centred around Christ’s teachings and displayed deep empathy and expressions of Christian faith.Of interest was the sculpture “Doppelgesicht” (Double face) where a woman's face had been hammered out of thin metal. The face looked different when viewed from the front and back. The idea of identity and the inner truth of a person versus the ‘outside’ face the world sees was a theme that Gross would revisit throughout his life.

The exhibition moved to the Galerie Wasmuth in Berlin in 1957. A review from the Telegraf on the 13th of January of that year noted that Gross’ work was typical of early German Expressionist art and that his use of colour resembled that of stained glass windows which gave his paintings a sense of solemnity.

In 1963 Gross decided to make an unexpected move to Scotland. This decision may have been surprising to his friends as he had no real link to the Country. It would however be the beginning of a hugely important and fulfilling chapter in his life. His wife had a friend who lived in Scotland. They loved Gross’ work and introduced it to Karl König, who was a co-founder of the Camphill movement. The Camphill movement was started in 1939 in Scotland by a group of Austrian refugees. Based on Anthroposophical principles, their aim was to set up an intentional, therapeutic, community where children and adults with additional support needs could live and thrive with those that care for them.

Learn more about the Camphill movementAt the time, König was looking for artists to help create paintings and sculptures that would furnish the inside of Camphill Hall that was then being built in Scotland. This Hall was to be the spiritual and cultural centre of the Camphill Community there. After being introduced to Gross’ work König was impressed and subsequently, König and Gross met at Lake Zurich. The two men bonded over their strong Christian, spiritual and artistic beliefs. They both saw art's true purpose as awakening spirituality. As a result of this meeting Gross was invited by König to visit the Camphill Community in Scotland and in 1962 Gross and his wife made their first visit. Here Gross gave a talk and showed slides of his work. It was around this time that Camphill Hall was to be opened. König had asked Gross to create metal sculptures for the Hall as well as a set of stained glass windows. Konig requested that Gross carry the work out on site as he believed this would result in a more authentic process and outcome. Gross agreed and created the sculptures ‘Archangel Michael’, ‘Archangel Raphael’ and ‘A Praying Man’ as well as a large set of stained glass windows.

Although Gross admitted that creating the huge metal sculptures was a task that tested his patience, he enjoyed working in the community and thought its purpose was an important one. He saw the importance in renewal, of resurrection, especially after the destructive nature of the war and he saw the Camphill Community as a necessary step in the right direction.

Gross and Sand were invited to stay and Gross became an artist-in-residence in the community.

This move facilitated a change in the way Gross viewed his lived experience as an artist.

Gross no longer strove for a ‘career’ and stopped promoting himself. Rather, he saw merit in being able to imbue the spiritual meaning and principles of his work to the community through his art.

In Camphill the child was the centre of the community and so the child became the main focal point of Gross’ work. He did this with care and empathy and the results were paintings that did not over-sentimentalise children. Showing them in an honest and open light, Gross portrayed their relationship towards each other and the adults that cared for them.

“Gross, like Konig, was aware that the kind of social renewal they sought could only be achieved by creating a world that was more responsive to the needs of the child. This is social art, where the medium is being used to convey an ethical message, not simply about how one should care for and protect children but how societies, in general, should treat all vulnerable groups”

Dr Robin Jackson

As an artist-in-residence Gross created many artworks that were hung in the various houses, meeting rooms and offices throughout the community. Importantly, he did not put any titles to his work. He was more interested in the viewer’s organic experience of perceiving his art. The abstract nature of his paintings meant that, for people living in the houses where they were displayed, new aspects or details would reveal themselves to the viewer after they had lived with the painting for months or even years. The paintings also acted as a source of meditation, where a co-worker could reflect on their practice and also be reminded of how life in the community may be being experienced by a child in their care.

“I felt the whole conception of artists in the Western world was wrong - that doing must replace philosophising about art”

Gross saw it as important to demystify the concept of ‘the artist’. He wanted his art and himself to be accessible to the community and so he took on pupils to teach. To those that knew him, Gross, although initially a quiet man, was funny, friendly and a great listener. He took mentoring his students seriously. Gross encouraged his students to fully immerse themselves in the experience of making and ‘doing’ art. He emphasised the importance of striving for honesty and not to fall into cliches. The end result was less important than what could be learned by the experience.

Gross would occasionally talk to his students about youth in Paris. One story involved working with other artists in Picasso’s studio. Gross greatly admired Picasso for “his humanity and his art”. For Gross, Picasso had a great influence over his formative years as an artist. He spoke of a time when one of the other artists had annoyed Picasso so much that Picasso had thrown the whole group out of his studio. Gross was very upset by this but soon after, Picasso allowed Gross to see him again. Picasso then signed the bottom of a blank piece of paper and gifted it to Gross. He told him that if he were ever in dire straits he was to paint whatever he wanted on that piece of paper and do what he felt was right with the work. Gross was greatly flattered by this gift and felt it illustrated how Picasso saw him as someone he could trust. Gross treasured this piece of paper for the rest of his life and fortunately never needed to use it (Jackson 2008).

Another student of his relayed that during the war, Gross had gone to see Picasso in his studio in Paris. Whilst there Gross, realised he was wearing his German army uniform, thereby confirming him as the enemy. He felt deep shame and apologised to Picasso. In response, Picasso told him that he didn't see the uniform, only the artist within (Imhof-Cardinal, 2008).

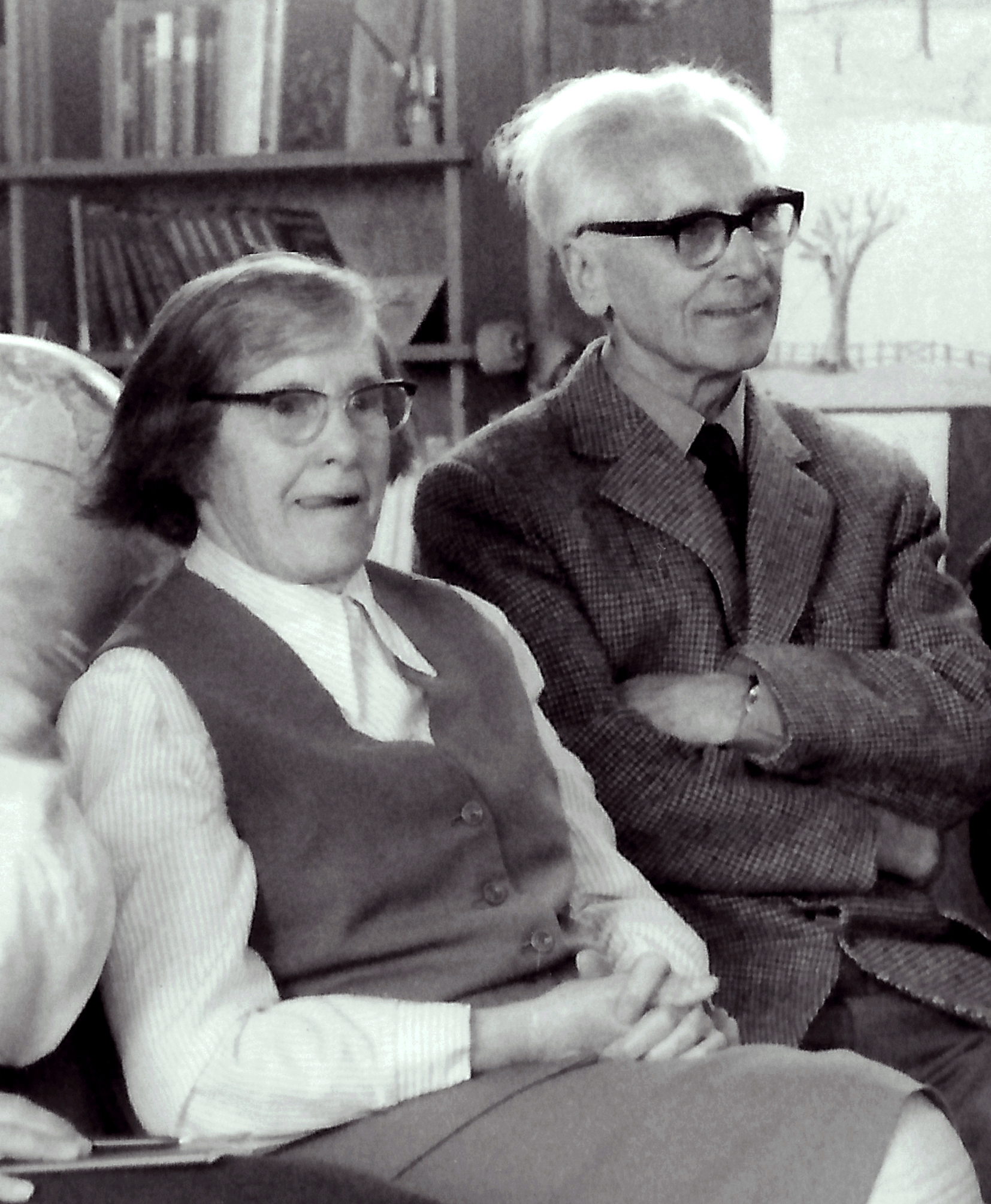

Hermann Gross with his wife Trude Sand, captured at Camphill, January 1985. (Camphill Correspondence, 1989) cited Robin Jackson ‘Art and Soul'

Gross lived the rest of his life in the Camphill Community. He taught, painted and created sculptures. He holidayed with his wife in a camper van where he travelled all over Scotland sketching what he found. He was a loved member of the community and greatly admired by his students and those that knew him. As he grew old, members of the community built him a home with a large studio.

Perched at the top of a hill, Gross spent his time painting in this light and airy room, where a wall of windows overlooked the river Dee and forests beyond. Hermann Gross died in September 1988 and was buried in a graveyard nearby, from which the community he was a part of for so many years can be seen.

This website would not have been possible without the invaluable work of Dr. Robin Jackson. Dr. Jackson has worked extensively to tell the Hermann Gross’ story, his book “HERMAN GROSS: ART AND SOUL” Offers an in-depth look at the artist’s life, art and influences. The book is currently available on Amazon for purchase.

view Book